What are the differences between Innate and Adaptive Immunity?

The main differences between Innate and Adaptive Immunity lies in their response mechanisms and specificity. Innate immunity is the body’s first line of defense and provides a rapid, non-specific response to infections. It includes physical barriers (like skin), chemical barriers, and immune cells like macrophages. In contrast, adaptive immunity is specific to particular pathogens and develops over time, involving specialized cells like T and B lymphocytes that create memory for future immune responses.

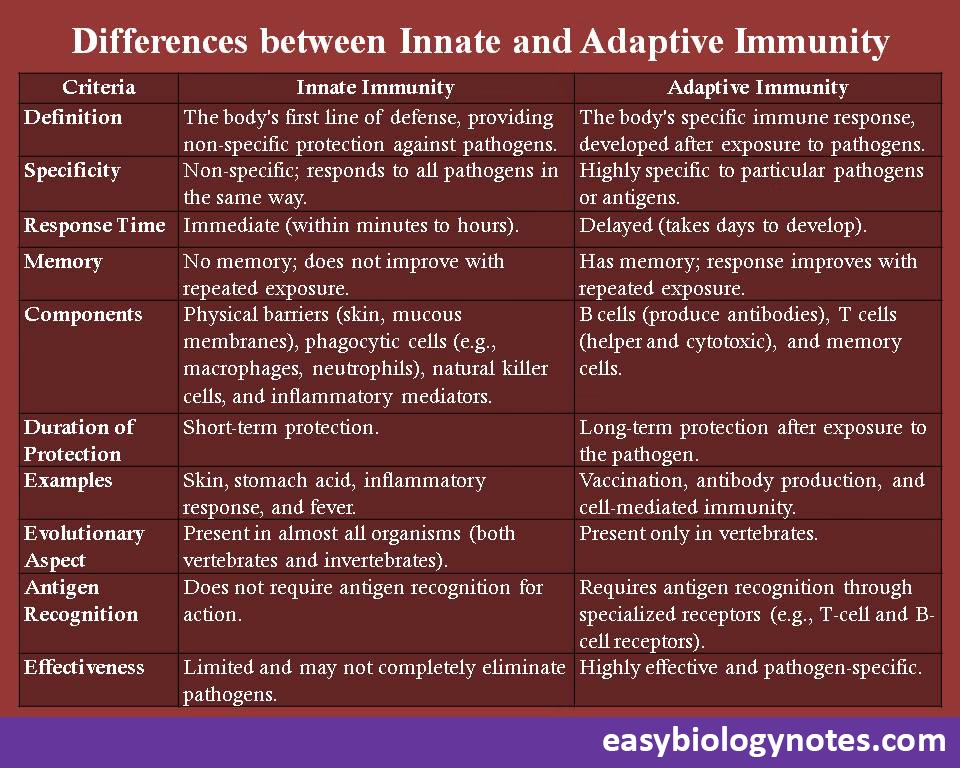

Following are some more differences between Innate and Adaptive Immunity -:

| Criteria | Innate Immunity | Adaptive Immunity |

| Definition | The body’s first line of defense, providing non-specific protection against pathogens. | The body’s specific immune response, developed after exposure to pathogens. |

| Specificity | Non-specific; responds to all pathogens in the same way. | Highly specific to particular pathogens or antigens. |

| Response Time | Immediate (within minutes to hours). | Delayed (takes days to develop). |

| Memory | No memory; does not improve with repeated exposure. | Has memory; response improves with repeated exposure. |

| Components | Physical barriers (skin, mucous membranes), phagocytic cells (e.g., macrophages, neutrophils), natural killer cells, and inflammatory mediators. | B cells (produce antibodies), T cells (helper and cytotoxic), and memory cells. |

| Duration of Protection | Short-term protection. | Long-term protection after exposure to the pathogen. |

| Examples | Skin, stomach acid, inflammatory response, and fever. | Vaccination, antibody production, and cell-mediated immunity. |

| Evolutionary Aspect | Present in almost all organisms (both vertebrates and invertebrates). | Present only in vertebrates. |

| Antigen Recognition | Does not require antigen recognition for action. | Requires antigen recognition through specialized receptors (e.g., T-cell and B-cell receptors). |

| Effectiveness | Limited and may not completely eliminate pathogens. | Highly effective and pathogen-specific. |

Elaborative Notes on Differences Between Innate and Adaptive Immunity

The immune system is a highly developed and complex network of biological processes that protects organisms from pathogens and other harmful agents. At its core, it comprises two complementary arms: innate immunity and adaptive immunity. While both play essential roles in safeguarding the body, they exhibit significant differences in their mechanisms, specificity, and memory. This conclusion explores these distinctions, their biological implications, and the collaborative nature of these immune responses.

1. Overview and Functionality

- Innate Immunity:

Innate immunity is the body’s first line of defense, providing rapid but nonspecific responses to potential threats. It includes physical barriers (like skin and mucous membranes), cellular components (such as macrophages and natural killer cells), and chemical mediators (like cytokines and complement proteins). This system acts immediately to prevent the establishment and spread of infections. - Adaptive Immunity:

Adaptive immunity is a highly specialized defense system that develops over time in response to specific pathogens. It is characterized by antigen recognition, clonal expansion, and memory formation. Key players in adaptive immunity include T cells and B cells, which work together to neutralize or eliminate pathogens effectively.

The division between these two systems demonstrates a strategic approach to immune defense, with innate immunity serving as a broad protective shield and adaptive immunity providing precise, targeted responses.

2. Response Time and Specificity

- Innate Immunity:

The innate immune response is immediate, typically occurring within minutes to hours of pathogen detection. However, its nonspecific nature means it targets broad patterns found in many pathogens, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or flagellin. - Adaptive Immunity:

Adaptive immunity, on the other hand, requires time to develop. The initial activation of adaptive responses can take several days to weeks, as antigen presentation and clonal expansion occur. However, once activated, the response is highly specific, targeting unique antigens on the pathogen.

This difference highlights the complementary roles of these systems: innate immunity provides immediate protection, while adaptive immunity delivers long-term, precise defense.

3. Memory and Longevity

- Innate Immunity:

The innate immune system lacks memory. Each encounter with a pathogen triggers the same level of response, regardless of prior exposures. - Adaptive Immunity:

Adaptive immunity is defined by its ability to “remember” pathogens. Memory B and T cells are generated after the first exposure, allowing for faster and more robust responses during subsequent encounters. This principle underlies the effectiveness of vaccines, which prime the adaptive immune system for future protection.

The presence of immunological memory in adaptive immunity ensures long-term protection and underscores its role in preventing reinfections.

4. Cellular and Molecular Components

- Innate Immunity:

Innate immunity relies on a diverse array of cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells. These cells recognize pathogens through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) like toll-like receptors (TLRs). - Adaptive Immunity:

Adaptive immunity involves lymphocytes, specifically B cells and T cells. B cells produce antibodies, while T cells can either directly kill infected cells (cytotoxic T cells) or assist other immune cells (helper T cells). The specificity of adaptive immunity is mediated by antigen receptors unique to each lymphocyte.

The cellular diversity of the innate system and the antigen specificity of the adaptive system demonstrate their tailored approaches to combating infections.

5. Role in Pathogen Elimination

- Innate Immunity:

The innate immune system acts as the initial responder, limiting pathogen spread and alerting the adaptive system. For example, macrophages engulf pathogens, and complement proteins create pores in bacterial membranes. - Adaptive Immunity:

Adaptive immunity takes over when pathogens evade innate defenses. Antibodies neutralize toxins and pathogens, while cytotoxic T cells destroy infected cells. Additionally, helper T cells orchestrate the immune response by activating other immune cells.

The sequential activation of innate and adaptive immunity ensures a layered defense, with each system compensating for the other’s limitations.

6. Role in Immunological Disorders

- Innate Immunity:

Dysregulation of innate immunity can lead to conditions like chronic inflammation, autoimmune diseases, or sepsis. For instance, excessive activation of innate responses may result in tissue damage. - Adaptive Immunity:

Malfunctions in adaptive immunity can lead to severe diseases, including autoimmune disorders (e.g., lupus, rheumatoid arthritis) and allergies. These conditions arise when adaptive immunity mistakenly targets the body’s own tissues or benign substances.

Understanding these dysfunctions highlights the delicate balance required for effective immune regulation.

7. Evolutionary Perspective

- Innate Immunity:

Innate immunity is evolutionarily ancient, found in all multicellular organisms. Its conserved mechanisms reflect its fundamental role in survival. - Adaptive Immunity:

Adaptive immunity evolved later, primarily in vertebrates. Its complexity and specificity have enabled vertebrates to thrive in diverse environments and face evolving pathogens.

The evolution of adaptive immunity complements innate immunity, creating a robust system capable of addressing both immediate and long-term challenges.

Conclusion

Innate and adaptive immunity represent two integral components of the immune system, each with distinct roles that collectively protect the body from harm. While innate immunity offers immediate, nonspecific protection, adaptive immunity provides a tailored and enduring response. This interplay ensures comprehensive defense against pathogens, with innate immunity buying time for the adaptive system to mount a specialized attack.

The key differences between these systems—response time, specificity, memory, and cellular components—reflect their complementary nature. Innate immunity serves as the frontline defense, recognizing broad pathogen-associated patterns, while adaptive immunity focuses on antigen-specific responses, providing long-term protection through immunological memory.

Beyond their functional roles, these systems have profound implications for medicine and biotechnology. Vaccines harness the power of adaptive immunity, training the immune system to recognize and combat specific pathogens. Meanwhile, therapies targeting innate immune pathways are essential for managing inflammation and preventing sepsis.

Understanding the differences and interactions between innate and adaptive immunity has advanced our knowledge of immunological health and disease. From combating infections to developing immunotherapies, these systems form the foundation of modern immunology. Their seamless coordination ensures the survival of organisms, highlighting the complexity and efficiency of the immune system.

In conclusion, innate and adaptive immunity are not isolated entities but interconnected systems that work together to protect the body. Their study continues to reveal insights into the mechanisms of life, driving innovations in healthcare and underscoring the intricate balance that sustains health and immunity.